Introducing Themis Consensus Extension v1. A Solution to MEV for Application-specific Blockchains

Miner Extractable Value (MEV) is a fundamental problem of blockchains, described in a number of studies including Flash Boys 2.0. The power of miners to decide over transaction order and to censor transactions is a form of insider trading, where an intermediary party has knowledge about future events and can capitalize on this information, thus creating an unfair system.

MEV is a hard problem in decentralized systems and current popular blockchains such as Ethereum were designed at a time when transaction order fairness was not taken into account. MEV is shifting power from users to miners and we consider it the most pressing problem in crypto.

There are generally two approaches to solving MEV: MEV redistribution and MEV minimization. MEV redistribution is chosen by projects like Flashbots, which create off-chain markets to distribute MEV to miners and searchers. Themis is a solution for MEV minimization, as it does not take MEV from users in the first place. It’s more capital efficient to not take money in the first place, rather than trying to redistribute it after it has been taken.

We are excited to present our solution to MEV. This solution is optimized for DEX-specific blockchains but may serve as inspiration for wider app-specific use cases. We’ve chosen the name Themis Consensus Extension, as Themis is the Greek goddess of justice. We believe it will bring more fairness and justice to DeFi.

For this article, we make the following assumptions:

- We use the term Miner, but it applies to Validators on Proof of Stake networks too.

- The User is a light-client participant and we omit the fact that the Miner is a user too.

- We assume that only unconventional MEV is considered under MEV, because conventional MEV is treated as mandatory for blockchains to work (transaction fees and block rewards).

- We’re not using the notion of good/bad MEV because we posit that older definitions of MEV highlighted the problem better. The problem is that miners have more power than users, rather than which type of extractable value is good or bad in itself. For example, arbitrage is unfair if users have no chance at claiming this value.

We’re confident to say it’s a reasonably complete solution to MEV, that works in a permissionless setting and uses only traditional cryptography. With modifications it should work well for both PoW and PoS networks.

The article structure:

- MEV powers

- VER: Value Extraction by Reordering

- VED: Value Extraction by Denial

- Introducing Themis Consensus Extension

- Solution to VER

- Solution to VED

- Common questions

- Future areas of research

- Conclusion

MEV powers

We propose that all value extraction is fundamentally coming from two abilities. A power to reorder transactions and a power to deny transactions. We define the terminology in the following way:

VER: Value Extraction by Reordering

This power belongs to the network participant who is bundling the transactions in the block and can determine the order of execution. By knowing the order, the attacker can put its own transactions either before or after user transactions and capitalize on it. There are more sophisticated ways of reordering that relate to types of interacting smart contracts or transactions on the chain, but we think the label ‘reordering’ covers the spectrum well.

VED: Value Extraction by Denial

This power belongs to any network participant that is relaying transactions from a user (client) to the block. By having the power to decide whether a transaction will be included or not, the attacker can decide to reject the transaction or replace it with their own.

Usual attackers are centralized relayers (think Infura service on Ethereum) or miners who are responsible for gathering transactions from the mempool.

We believe that for the elimination of MEV, we need to prevent these two powers or minimize them as much as possible.

Introducing Themis Consensus Extension

Themis Consensus Extension prevents both VED and VER, in this particular way:

Solution to VER

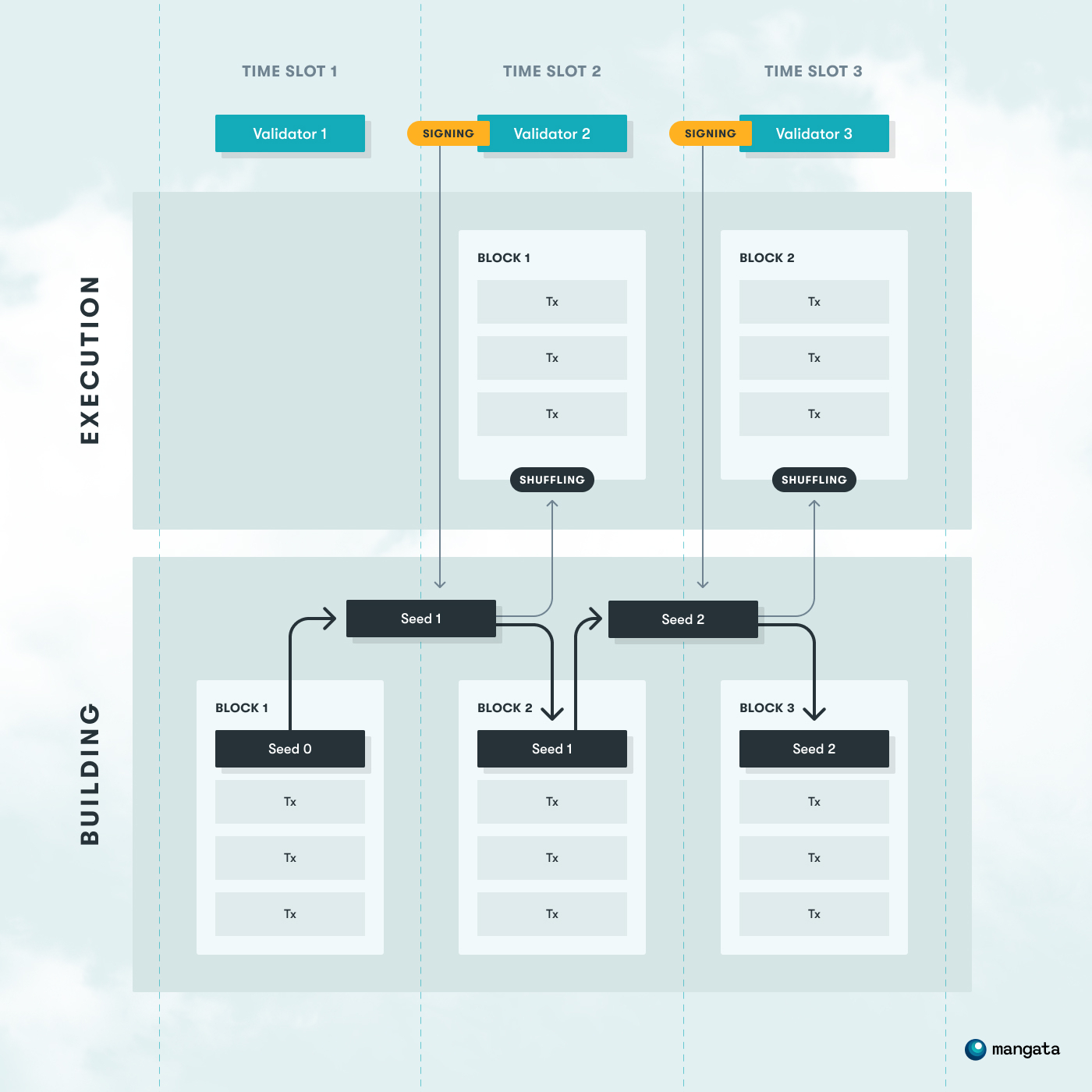

VER solution builds on the assumption that block production consists of two responsibilities: deciding on block contents and deciding on execution order. We propose to split the block production into a two-step process, block building and block execution, where in the first step transactions are accepted into a block (“block building”) and in the second step the transaction execution order is shuffled using information that doesn’t exist at the block building time (“block execution”). Every miner has a responsibility to build the new block and execute the previous block.

In the first step, the block builder gathers the transactions from the mempool and builds the block. After that, they provide a seed for the subsequent miner that will use it for shuffling the transaction execution order.

In the second step, the block executor signs the seed with their private key and uses that as a seed for shuffling. A private key is used because it’s unknown to the block builder and can’t be manipulated by the block executor. The signature is not malleable and the scheme is deterministic. After that, the executor builds a new block (performing the first step for the next block) and provides the private-key-signed seed.

This effectively creates a seed chain that is used for transaction shuffling.This separation of concerns guarantees that the block builder can’t affect the execution order and the block executor can’t set the block content and has to shuffle the transactions.

In consequence, this creates a 2-block HEAD of the blockchain, and doubles the time of the block execution.

This solution introduces probabilistic value extraction. In the suggested design, participants will have a higher chance to claim any pure gains by sending multiple transactions, and we argue it is fair since every participant has equal opportunity. In other designs, even with Flashbots auctions, the power is shifted more towards miners, who are the ultimate decision-makers over the block content. At the same time in Themis Consensus Extension participants are disincentivized to attempt to extract any gains with multiple transactions, thus eliminating an edge that is making frontrunning activities statistically profitable.

More technical specifications can be found on this page (Substrate framework specific): https://github.com/mangata-finance/mangata-node/blob/develop/Mangata.md

Solution to VED

An example of a common VED attack is denying pure gain transactions (e.g. arbitrage) and replacing them with their own. We argue that if only miners have this possibility, it’s an unfair design because such a pure gain opportunity is never available for a user.

There are 3 levels of VED solutions, from least to most robust:

- Miners shouldn’t deny transactions

- Miners don’t know which transaction to deny

- Miners can’t deny transactions

Current state of VED solution reaches the 2nd level of robustness that the Miner (or any transaction relayer) doesn’t know what to deny, because it has no information about the transaction purpose.

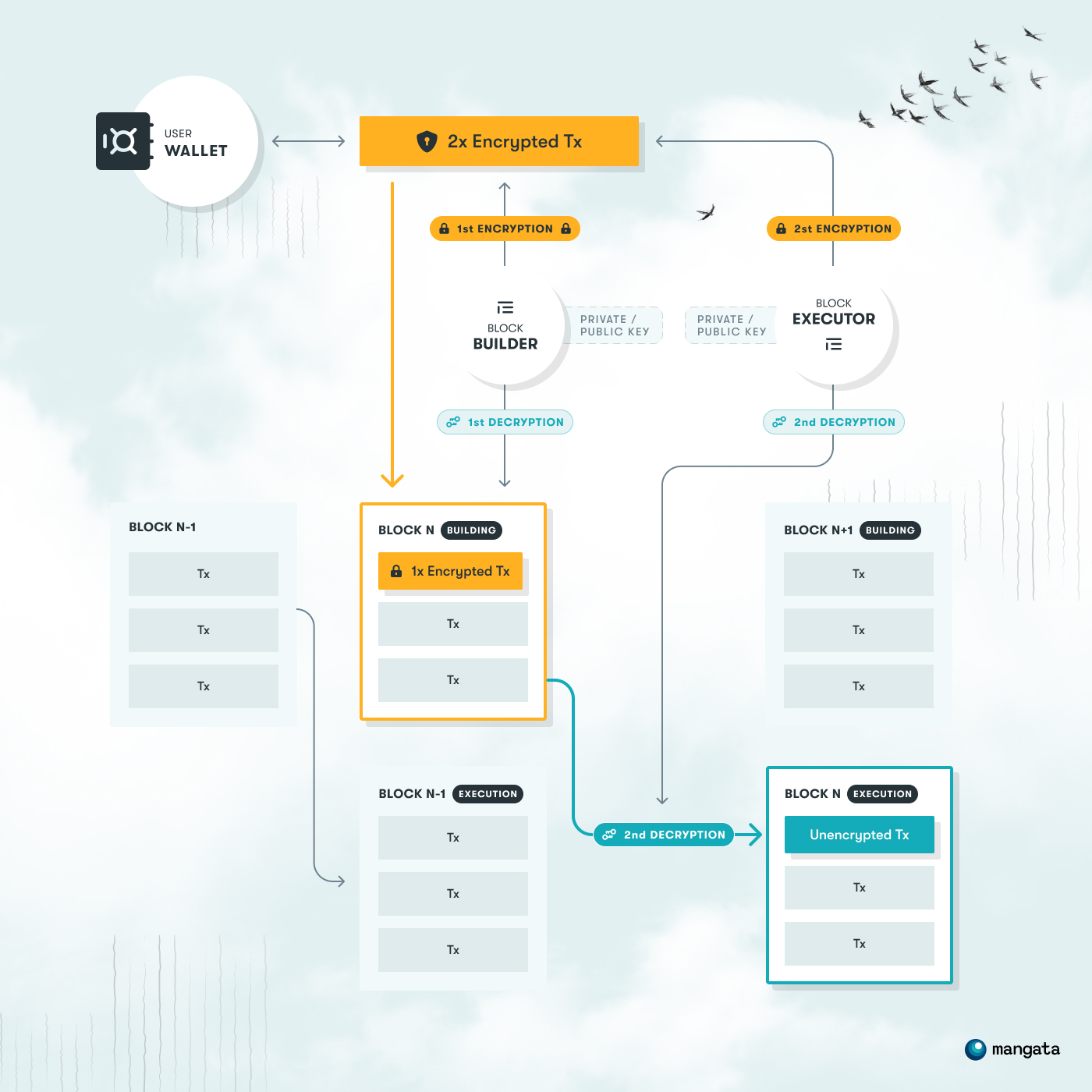

To achieve this, we propose the encryption of transactions by the user, that can be decrypted only by the transaction executor, given it’s been first decrypted by the block builder. It’s achieved by transactions being encrypted by public keys of both the block builder and block executor. This creates a doubly encrypted transaction that is sent to the mempool.

In the following steps, block builders are required to decrypt the transaction, but that doesn’t reveal its content to them because the transaction still requires a final decryption from the block executor. In this approach, the transaction builder can’t know the content of the transaction, but the executor is forced to decrypt and execute it. This means that block builder and block executor have to be known ahead of time and submission into the mempool is not node-agnostic, but has to include that foreknowledge.

It is important to note that transaction encryption is voluntary and should be used only where it is reasonable. This is because processing an encrypted transaction is costly and the processing costs are not guaranteed to be covered by the economic value created by transaction processing. In fact, since the content of the encrypted transaction is unknown, it may even be impossible to execute. This is why, unlike unencrypted exchange transactions, all encrypted transactions are required to have fixed gas costs.

A more technical specification of the VED solution will be available on the wiki soon.

Common questions

Is this receive-order or send-order fair?

Instead of relying on order fairness, we rely on randomized ordering, thus giving every participant an equal opportunity.

How do you approach probabilistic extraction?

Probabilistic extraction requires multiple transactions to be sent to increase the chance to extract the value. However if the user’s transaction index within the block is taken into account for the shuffling, only one transaction from a single account will have a chance to be placed before the user’s transaction, no matter how many were sent.

At the same time, every participant can transact from multiple accounts. Failed or canceled exchange transactions that are included in the block and executed are subject to the exchange commission too. This addresses probabilistic extraction in this case. Since it is an exchange commission percentage that defines the profitability of the exchange value, paying it several times reduces the possible profit of the extraction. Even a requirement for a single additional exchange transaction significantly reduces the number of extraction opportunities.

In the case of non-exchange transactions, we believe that having a higher chance of getting the profit by sending more transactions is fair since every participant has equal opportunities.

Probabilistic extraction incentivizes bloating the network with spam transactions. What’s your approach to this?

In our case, we’re building an application-specific blockchain, optimized for a decentralized exchange use case. The transactions have fixed fees and no gas costs (no fee market on the blockchain). In our design, failed transactions pay fees as well, making the spam costly. Thus, supplying many transactions decreases the profit, creating a natural cap on how many transactions of a certain amount is reasonable to send in an attempt to extract the profit (the same way as there is a cap on how much gas one can pay competing for position inside the block on Ethereum without Flashbots auction)

How do you solve the case when a user sends multiple transactions where their order is dependent on each other?

The shuffling in the VER solution is done in a way that preserves the order of transactions being done from the same account but is shuffled within all other transactions in the transaction set.

How is the user transaction guaranteed to be decrypted in any future time X?

If included into the block, the transaction executor should decrypt and execute it. If the transaction is not executed by the corresponding executor, it can be proven the executor misbehaved and will be slashed.

What if the transaction is not decrypted within the existing set of Block Builder / Executor? How can future executors and builders always decrypt the transaction?

They can not. But non-designated block builders can include the transaction into the block, making it mandatory for the designated block builder and executor to decrypt their part. It is trivial to prove they misbehaved if they have not decrypted the transaction which is already included in the block, and the block is known to them.

If the current block builder didn’t decrypt all transactions that they should’ve decrypted, the transactions are waiting in the mempool until the block builder is elected again, by the respective PoS or PoW mechanism. This introduces a new class of attack vectors. Because of it we will need to ensure that encrypted transactions do not cross session boundaries. In some PoS consensus mechanisms like Aura (which is used for Substrate parachains currently) a user can specify when exactly they want the transaction executed.

How is randomized ordering affecting the resulting price of a trade? How can I be sure it’s a better price?

In MEV redistribution the common user is positioned last in the redistribution chain, and they are usually left with the worst price possible, unless they deploy more sophisticated MEV searcher strategies. In randomized ordering set, the price is statistically equitable for all participants in a big enough set of trades.

Future areas of the research

What known attack vectors do we have currently?

- Statistical attack with a non-exchange transaction, which is possible because of respecting the nonce order for the account. It will allow spending more on fees to increase the chance of getting to the right spot in the block. Grouping transactions by the sender and shuffling subsets of transactions from different groups but with the same index inside the group is the solution.

- Total denial of any transactions except one by a block builder. It allows the block builder to extract a pure gain, e.g. arbitrage, given that gain opportunity is bigger than the sum of the fees of excluded transactions. However one can argue that if arbitrage (or other opportunities) is not taken in the block where the opportunity arises, the following block builder has the fair right to claim it for themselves.

- Collusion of several parties to extract the gains. The current version of the protocol assumes the malicious actors are behaving on their own. Situations when several miners collude to extract gain from users should be detectable and/or punishable.

What will we solve in the next iteration of this solution?

- Statistical attack with non-exchange transactions.

- Better management of encrypted transactions.

- Introduce a solution to detect cooperating malicious miners.

What is the failure possibility of encrypted transactions? Can we mitigate it in the future?

It is planned for the next protocol iteration.

The collusion of both Block builder and Block executor together. What is the direction of a solution for this problem?

Collusion should either introduce a direct punishment for the colluding parties or be detectable by any user. The exact solution will be introduced in a future protocol version.

Conclusion

Themis Consensus Extension is presented to be a solution for MEV on application-specific blockchains. It is fully implemented by Mangata DEX blockchain, and is suitable for other applications as well. The current iteration of the protocol is focusing on the removal of powers causing MEV from any network participant, making them more equal. As a result, entire classes of value extraction activities are not possible on the protocol, resulting in fair execution without order fairness and guaranteeing a better price for the users compared to similar applications where value extraction is possible. The current design of the protocol is best suited for PoS consensus where the order of entities building the blocks is known in advance, however, it can be adapted to a consensus protocol without this property with reasonable effort. This solution should be accounted for in the transaction encryption design of both light clients and wallets. At the same time fee estimation algorithms won’t be needed. In consequence, privacy is enhanced too, because the transaction intent is hidden until it reaches the execution.

Since Themis Consensus Extension is designed for application-specific blockchains, each implementation should consider and analyze MEV opportunities presented in the application and validate measures introduced by the protocol are sufficient to prevent value extraction. The current design assumes the malicious actors are acting selfishly and with no cooperation with others. The next versions will solve detecting and punishing collusions of the minority of participants. It is important to note that due to the nature of decentralized consensus byzantine tolerance no protocol can stop and punish malicious collusion if the majority of participants is involved in it.

This solution has been implemented in the Substrate framework using the Rust programming language, within the AURA consensus and will be connected as a parachain in the Polkadot network. You can check the repository here: https://github.com/mangata-finance/mangata-node

Watch the technical deep dive

We went into the technical implementation at the Sub0 conference hosted by Parity Technologies:

The research is led by Gleb Urvanov. Thanks to Xinshu Dong, Luke Pearson, Will Wolf, Peter Kris, Marcin Gorny, and the whole team at Substrate Builders for contributing comments and ideas.

Stay tuned for the blog updates

Subscribe to the newsletter and follow Mangata on social media.